Moving from the big screen to the small screen, it’s time to talk about:

TV

As I continue towards approaching my personal media singularity i.e. the most I am able and comfortable with reading, watching, and listening to in a year, television has become the first medium I no longer have any interest in keeping up with. This is a medium I explore in exclusively non-critical domains and very sparingly when I know I want to watch something without feeling the need to write about it. Still, I did watch a few shows this year and have some recommendations I thought I’d include. They are as follows:

Cross

Trunk

Shrinking Season 1

Beef

The Auditors

Mr. and Mrs. Smith

Doctor Slump

Love Next Door

Queen of Tears

There are a lot of Korean Dramas on this list, and they are most of what I look toward when I decide to find a show to watch. Many K-Dramas offer a fairly rigid and precise structural format I’ve grown to appreciate while also having a lot of narrative variability. What I mean by this is that the majority of K-Dramas have 16 or 12 episode formats, and many are made with the assumption that there will not be a second season. Additionally, episode runtimes typically range from 50 to 75 minutes, and there are often two to four simultaneous plotlines in motion at a time. It’s nice to know I am getting a complete story with a varied cast of characters that is paced with a lot of intention.

That’s all I have to say when it comes to TV in 2024. I don’t really have any television-related goals for this year or anything, so for now I will move on to:

MUSIC

Being such a transient individual when it comes to all forms of media, it may not come as a surprise that any Wrapped statistics tend not to capture my listening habits very well when my most listened-to song was done so 12 times. Still, this year I listened to a record variety of albums in hopes of acquiring a sufficient 2024 musical acumen to not feel like an idiot on the Pierced Poets’ Party Podcast Album of the Year episode surrounded by amazing people who eat, sleep, and breathe music much more than I. Pierced Poets Productions is a Northeast Ohio-based music and event venture founded by one of my closest friends, Austin “Jax” Amadio that I encourage anyone interested in music or in the music industry to check out and support. I listened to 303 albums and 137 EPs in 2024, and there’s still a few I intend to catch up on before calling the year complete, even though there’s always more music. I have a lot to say about some of the albums that came out in 2024, but I may already have an established home for those words, so instead I will simply list my favorite albums of 2024.

Honorable Mentions

Dora Jar - No Way to Relax When You Are on Fire

JPEGMAFIA - I LAY DOWN MY LIFE FOR YOU

Jelani Aryeh - The Sweater Club

Nilüfer Yanya - My Method Actor

Novo Amor - Collapse List

Phantogram - Smitten

Remi Wolf - Big Ideas

Luna Shadows - Bathwater

Chloe George - A Cheetah Hunting in Slow Motion

Porter Robinson - Smile!:D

Jean Dawson - Glimmer of God

Charli XCX - Brat

EP of the Year: Chløë Black - Strange Little Bird EP

The List:

10. Hana Vu — Romanticism

9. Moony — Warning High Cube

8. Half Alive — Persona

7. Mui Zyu — nothing or something to die for

6. FLO — Access All Areas

5. FIG — FITS

4. Paledusk — PALEHELL

3. MICHELLE — Songs About You Specifically

2. Knocked Loose — You Won’t Go Before You’re Supposed To

1. Aaron West and the Roaring Twenties — In Lieu of Flowers

If any of my writings exist by the time this lives somewhere, I will share them here. I hope to continue listening to music at about the same pace and variety in 2025, continuing to discover new artists and discard those I no longer find as appealing. I did not only watch and listen in 2024, but also read both comics and:

PROSE

I only read eight books this year, which is a lot less than I had hoped. I have no excuse for this one either other than the first one being over 700 pages. There was just a large gap between March and September and then nothing before the end of the year. I have a few thoughts to share, but I’ll keep it sparse and also group books in the same series together.

Dune — Frank Herbert: Sorry to all the fans out there, but I found Dune to be… fine. The novel boils down to beautifully woven, intricate, prose masterfully piecing together a complex narrative that time and again proves profoundly stupid when it comes to the series of events that occur and the series of decisions characters make.

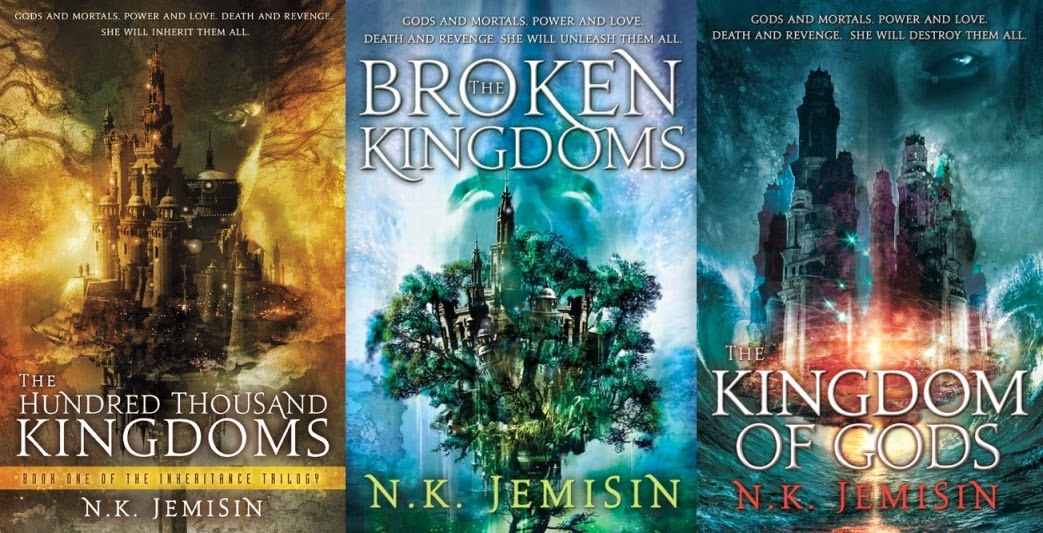

The Inheritance Trilogy (One Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, The Broken Kingdoms, The Kingdom of Gods) — N.K. Jemisin: This was my first foray into Jemisin’s fantasy work, and I found each book in the trilogy better than the last. Things started off a bit too simple and straightforward with One Hundred Thousand Kingdoms being a fight for royal succession played out as Jemisin moves the protagonist from situation to situation while describing what happens. There’s nothing too heavy to dive into, but Jemisin’s vivid descriptions and underrepresented setting provide a breath of fresh air to an often-told story. The Broken Kingdoms is a slight improvement on the first, largely because Oree is a much more interesting protagonist, and her powers and limitations are worth following. The interpretation of the struggles of a fallen god is a far more interesting story to iterate upon than royal succession. As a result, choices are more emotionally profound and the prose is more fantastically descriptive. The Kingdom of Gods proves to be the best of the three so far. A fallen trickster god, in the form of a child, turned mortal and forced to age and obtain responsibility alongside two mortals for which he has some feelings all while navigating heavy political intrigue. The most complex premise that plays out as cool as it sounds. By the end, its narrative becomes truly ascendant reaching the status of one of the better fantasy novels I’ve read. Jemisin artfully points out the cyclical nature of the universe, as she contemplates the inevitability of mortality, the pain and joy and intimacy of love, and so much more.

The Scholomance Trilogy (A Deadly Education, The Last Graduate, The Golden Enclaves) — Naomi Novik: The Scholomance Trilogy is simply a ton of fun. It has a great magic system and environmental construction. There is an excellently designed setting backed with a few very cool architectural diagrams, although I do wish the diagrams were in the front of the book. The visual layout is outstanding whereas the description shines when it sticks to languages, spells and creatures. El's voice shines brightly as she learns to feel more and care more about others with a few smaller lights from some of the supporting cast, but unfortunately Orion is just an empty shell of a human being, although that may be the point. The Last Graduate does some very great building off of the first book’s scaffolding and is an excellent step up. El learns to feel more where you can almost see her heart grow three sizes. Liu, Aadhya and Chloe shine brighter still while Orion remains an empty husk of a man until a single conversation towards the final act. The school evolving into a character of its own was great as well, although I'm not sure the final plan was the best one could've come up with given the constraints. Definitely felt like a solution Novik had to write herself out of. This is further proven in The Golden Enclaves which, while an excellent conclusion to the primary conceit of the series, manages to escape its central metaphor and sticky initial premise at the expense of the characters. Aadhya, Liu and even Leisel to a lesser extent lose their personalities at the expense of grander machinations so that events can happily wrap themselves up with a clever solution. That being said, I have to admire the overall message about the dangers of building the foundation of safety, security, and shelter for a select few on something rotten, poisonous and violent at its core, especially with the only solution being the acceptance that it will all have to burn down and one will have to start over from scratch. It’s a little on the nose and a bit too similar to The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, but it’s well executed and there’s a lot to be learned there.

The Years of Rice and Salt — Kim Stanley Robinson: It’s wild to me how little I see The Years of Rice and Salt mentioned in the concept of Kim Stanley Robinson’s legacy and authorship when it exists as a tome for crafting alternative historical fiction. There’s so much to comb through and learn from on all levels of the prose here from the sentence structure all the way through centuries of historical context. The story is told through the perspectives of three characters in 10 distinct scenarios across 10 epochs of this alternate history. At first, it feels as though on a macroscopic level, there isn’t a ton to grasp onto as far as how this one gigantic change (that being that the Black Death killed 99% of Europe’s population instead of about 33%) in world history has fully propagated years or centuries into the feature and around the globe. In any one epoch, you may know what’s happening to the three primary perspectives, whose souls are usually grouped together, but the rest of the world tends to exist in a sort of fog. Each new era we see incarnations of the characters during some sort of historical turning point/marker, and that can be pretty neat, but the early stories don't have a lot of emotional depth on a character level, so it takes awhile to get going. Perhaps I'd feel more if I were more in tune with my faith but alas, I just don't think there's a ton of personal emotion involved here. As such the real meat of this book occurs when looking with this sort of third-person, top down view. When the narrator is able to recount what happened to each character in one overall incarnation and basically sum up their lives for the reader is when the story becomes the coolest.

Luckily in between each era, there's a chapter where that takes place in an "ethereal land of divine judgement" which is a realm where souls go to to get judged and reincarnated. It looks different depending on the spiritual beliefs the characters hold at the time. There the characters are all waiting in line to be judged and they sort of reflect on that one life in the context of their past lives. I thought it was weird and tacky at the beginning and wasn't sure it worked, but the choice of transition won me over by the third or fourth epoch, and now I think it might be necessary in some ways. The novel follows three core personalities as their souls transfer from incarnation to incarnation, and these souls often have philosophies and core principles that can sometimes land at odds with each other. The “K” personality is one centered around a strong sense of righteous justice and self preservation. The “I” personality tends to value intellectual curiosity above all else, and the “B” personality has pure, but often naive, intentions in order to try and achieve the most good for the most people. The novel quickly demonstrates the values to society that exist in all three of these personas, how individually they can all be led astray, but together, these three personalities can produce immense societal change and become formidable opponents.

The three personalities are never in positions of sovereign leadership, although they often serve adjacent to, or in advisory roles for, those positions. Doing this allows Robinson to dismiss the “singular Great Man of history” theory while also not discounting the difference an individual’s impact is able to have. It strikes a great balance. The book’s length allows it to touch upon so much with regard to humanity, history, philosophy, ideology, faith and more, and it made The Years of Rice and Salt one of the most impressive novels I’ve ever read.

That’s it for prose in 2024. I’d say I aim to do better in 2025, but the two highest priority books on my list total 2000 pages, so I make no promises. For the final flavor of media on this list, I move to my favorite medium and one I am most accustomed to writing about. I’m quite nervous I attempt to dust any remaining skills I have off the shelf and get back to writing, as I was quite burnt out by the time I stopped, but it’s time to move to:

COMICS

Even following quite a bit of writing about 2024, I approach discussing comics with a lot of trepidation. Early 2017 was when I truly fell in love with the comics medium beyond just a casual appreciation, and from 2018 to early 2023, I was entrenched in writing about comics. By the time I lost any ability to write in 2023 about a form of expressions I loved so dearly, I also found myself extremely burnt out with the medium itself. At least, that’s what I thought. In 2024, it became clear to me that I wasn’t so much tired of the art form as I was with everything around the artform.

Writing about comics was the first time I grew the confidence to think that what I had to share had value. The more I expressed my authentic passion for something and the more that I picked up rhetorical and communicative skills that improved how that writing was received, the more I wanted to share and the more I wanted to participate in and learn about comics. I grew such a love and a passion for it that… I really do miss, even at a time when I was stressed out of my mind with school work and other university activities.

I was so enamored as well with the opportunities that came my way. The ability to talk to some of my favorite writers and artists because of my writing and the smallness of comics felt like a gift. The ability to meet people with the same passion as me in online and convention spaces was a blessing. But then, some burdens started to come along. I have always been a fairly stubborn fellow. I’d like to think that I was raised to be a fairly good judge of criticism, and so I would push back against a fair amount of editorial critique when I thought it was dampening my voice. I often pushed for restructuring and rewordings that met in the middle or took an entirely different approach to the same problem an editor may have had with my original writing. But at some point, multiple outlets decided to go all in on SEO at the same time. Some of this can be attributed to the rollout of new wordpress features, some of it was the pandemic and an increased operating cost coupled with decreased traffic to some of these sites. Some of it was my own internal reframing and the fact that I wanted more for my own writing. In the end, I was unhappy with the conventional review structure, unhappy with discussions of single issues, unhappy with the way positive reviews get rewarded and negative, nuanced critiques get ignored or slammed. Once authentic editorial voices like PanelxPanel started to shut their doors, I needed to take a break as well.

I always had a hope that I would find my way back to writing again, but I originally hoped it’d be exclusively creative in nature. What brought me back to a more critical space ultimately boiled down to what’s best articulated in Adolfo Ochagavía’s piece about the desire to broadcast. Broadcasting is the best term I’ve found for why I love writing and want to write, despite how difficult I often find it to be. Ultimately, I write as a means to share myself with more people in search of a connection. If my writing leads to a pleasant conversation with one more person, then it has worked. That’s likely always what I’ve been looking for, even if I didn’t know it. I took this realization as a sign to reaffirm a commitment to bare my soul in my writing, even if no one notices. Still, I fear that my critical abilities will fall short of my sincere aspirations, so please take this long-winded explanation as me psyching myself up to talk about comics again.

Comics come in so many different forms of varying sizes that it becomes quite difficult to quantify how much I read. All I can really say is that I read quite a bit more than last year, but not to a level to which I feel like I’ve really gotten my feet planted back into the medium. I will start with a few honorable mentions:

The Site — Fabien Grolleau (W), Clément C. Fabre (A & C), James Hogan (T)

Dawnrunner — Ram V (W), Evan Cagle (A), Dave Stewart (C), Aditya Bidikar (L)

Swan Songs #6 — W. Maxwell Prince (W), Martín Morazzo (A), Chris O’Halloran (C)

Return to Eden — Paco Roca, Andrea Rosenberg (T)

Lunar New Year Love Story — Gene Luen Yang (W), LeUyen Pham (A)

Blow Away — Zac Thompson (W), Nicola Izzo (A), Francesco Segala with assists from Gloria Martinelli (C), DC Hopkins (L)

Petar & Liza — Miroslav Sekulic-Struja, Jenna Allen (T)

Onto my top 9 of the year:

9. Search and Destroy Vol. 1 — Atsushi Kaneko (W & A), Based on Dororo by Osamu Tezuka, Ben Applegate (T), Phil Christie (L)

Search and Destroy Vol. 1 represents the upper echelon of narrative sequential image-making in the viscera and revenge subgenres. It is a relatively straightforward narrative about a girl and cyborg who may be more robot than human hunting down her missing body parts, 48 of them to be precise, that were taken from her and now live in the bodies of various elite cyborgs of the criminal underworld and oligarchical overworld. While narratively straightforward and conceptually simple, Kaneko makes this premise come alive primarily with his thin, sharp linework. In the style of Geof Darrow, especially in Hard Boiled, or Ian Bertram, Kaneko’s lines give texture to hair and fur as one of the few remaining organic touches Hyaku has left. They also pierce and cut. They give violence to movement and expose the raw flesh of Hyaku’s enemies.

In contrast, when the lines are more sparse after the battles have ended, there is a lingering softness which evokes the sense that there are still remnants of humanity within Hyaku. Atsushi Keneko is a cartoonist who proves keenly aware of how texture creates atmosphere, whether it be through the examples above or by paying particular attention to textured smoke effects in the middle of an action scene or glitchy effects and detailed circuitry during one of the final scenes toward the end of the first volume. The lettering FX are also extremely well-textured in their translation, which is also a touch I really appreciate considering the terrible working conditions and tight deadlines a lot of letterers and translators in the manga industry are subjected to these days. A lot of folks are expected to send out their fastest work over their best for very little pay, which is just one terrible blight amongst many in the industry.

Without these details, Search and Destroy would remain an action story you’ve seen plenty of times before. The tale of a seasoned, violent professional tracking down missing pieces of themselves (literal or figurative) and discovering or rediscovering parts of their humanity in the process is an old one. A more recent comparison might be that Search and Destroy is one of the best Wolverine stories ever told. The patchwork memory, painful implants, bouts of rage, and even the uncharacteristic kindness displayed towards children all invite such a comparison.

Doro provides a variant innocence contrasting with Hyaku’s search for blood. Her childhood spent in poverty while stealing just to get by leading to her impending death by messing with the wrong rich criminal helps shine a light on the rampant poverty of the dystopian future, the blatant evil of these criminal oligarchs, and also the repulsive nature of the individuals who would gladly harm a species into endangerment for amusement before driving it to extinction to collect their organs as rare trophies. It’s a story that finds triumph and justice in rage, and I look forward to the remaining two volumes coming soon.

8. Akane Banashi Vols. 1-9 — Yue Suenaga (Story), Takamasa Moue (A), Stephen Paul (T), Snir Aharon & Vanessa Satone (L), Keiki Hayashiya (Rakugo Supervision)

Akane Banashi is, far and away, the most compelling and talented ongoing manga in Weekly Shonen Jump’s catalogue. Sports manga, while my favorite genre, is not always the most popular genre in Japan or abroad, even with the success of stories like Slam Dunk or Haikyuu!!. The more niche the sport is, the harder it is to reel in readers. In the case of Akane Banashi, rakugo isn’t really a sport, but rather an artform, a 400-year-old artform of live comedic and dramatic storytelling onstage with limited movement and props, to be specific. This is also not a pastime that may be considered inherently popular to young people in Japan today, much less those abroad who may never have heard of the art form. This is all to say that Akane Banashi’s very premise is one fighting an uphill hill battle that it clears from the first volume.

I’ll start by clarifying Akane Banashi’s place within the classic sport’s manga framework. While rakugo is not a sport, the manga positions it as one by making the focal point of most chapters, as well as larger arcs, competition rather than simply performances. The eye of the narrative is always on the next competition as a means of advancement, and while all of the characters love rakugo as a means of expression and find value simply in performing, nothing ignites one’s drive like the fires of competition. On top of that, rakugo is framed like a sport through its team-like hierarchical structure. Individuals train within and advance in rank under various schools led by masters of the artform. These schools may be thought of as teams during larger competitions that seem to rarely occur between members of different schools and in a broader sense of ideological reverence and stylistic respect, but that is where the similarities end, because within each school lies the greatest sense of competition. Akane, along with her peers, train under individual masters who are, themselves, vying for the top spot as the next head of the school. There is a fairly immediate sense that there are only so many slots at each rank, so there is little room for failure if one wants to get promoted. There is a sense of comradery amongst those who train under the same master and even within the rakugo community as a whole, but that comradery only lasts until the competition begins.

Positioning Akane Banashi in this way are all sensible narrative choices and they are executed to the highest degree. It is also able to break a few pitfalls of the genre through being about an artform like being able to include a wide variety of ages. Akane may be around high school age to match the demographic of Weekly Shonen Jump readers, but her peers come in a wide array of ages which provides a welcome variety to the familiar heirs of competition.

Still, while competitions provide stakes, it normally wouldn’t be enough to make a series like Akane Banashi as good as it is. What Akane Banashi is able to do so well is convey the power of a verbal mode of storytelling through a sequential image form. Think about that. Rakugo is a verbal artform. It is an artform meant to move the audience with stories via the storyteller’s manipulation of gestures and their own voice. Manga is a sequential artform with frozen panels and no sound. So how does Akane Banashi accomplish this?

It starts with a very pragmatic approach to design. We often talk about an artist’s style or quality when it comes to their art, but they’re overall design and approach can be equally as important. Rakugo is an artform where a single individual on stage attempts to move an audience with little or no background. The manga reflects this with a focus on high panel counts, sparse backgrounds unless a detailed setting is necessary, and an extremely intentional focus on facial expressions and body language. Most of Akane Banashi consists of characters talking. In fact, most of Akane Banashi consists of characters talking about how to talk so that others will feel. In order to do this effectively, the reader can never be in doubt as to how a character on the page is feeling. When the reader is in doubt, then any ethos the character is supposed to have as far as their ability to make an audience feel is absent. If Suenaga and Moue fail in how they convey a character’s emotion to the reader, then that character becomes and remains a failure in the manga.

The consequence of this is that character design and facial expressions become priority. The faces in Akane Banashi are simple but nuanced. They are clean, and defined without an overreliance on a high number of lines. They are faces that can portray an extreme range of emotions and expressions, from fits of anger, to slight annoyance, to subtle smugness, to moments of triumphant joy, all of the characters in this manga need to be able to be shown at that level of artistic and expressionist range to convince the reader that they are good storytellers. The reader feels what the rakugoka feel so that they believe that the audience feels what the rakugoka feels. This same level of attentiveness also applies to gestures and fashion choices.

Akane Banashi also sets itself apart by making the lettering part of the art. In an ideal comic book industry, this would also be the case, however, under less than ideal working conditions and tight deadlines, manga lettering sometimes resorts to what makes for a baseline satisfactory presentation. Akane Banashi cannot afford to do this because what is being said in the text has such a strong overlapping connection to what is being visually depicted. In the easiest terms, a familiar expression is show don’t tell, but in this case, what is being shown is one person telling a bunch of other people a story. Have you tried to tell someone a story someone else told you? Does it hit the same? Can it capture the same magic if you explain that someone else told you this story first? It’s the same premise here. There are two layers to pass through to get into the rakugo story and the mangakas have to turn that into one each time a rakugoka performs. To do this, the letters employ a variety of techniques such as playing with balloon size, shape, outline and placement, font size and type, and including small cartoons within the balloons themselves to add dynamic qualities to the text itself.

When rakugoka tell stories in Akane Banashi, there are typically about 5 or 6 things that can happen at once. First is the present moment where the rakugoka is telling the story. What is visually shown in the panel is the rakugoka making various expressions and gestures on stage as well as some reactions from the audience. When the story is being told in this mode, the balloon outlines will be squiggly, amorphous, and bold.

The balloons almost look as though they are from a scroll unfurling. It depicts a sense of an ancient story being read. It sends the words being spoken through time. It echoes the varying voices and expressions the rakugoka is conveying even while the bold outline clearly separates the voice of the story from the visuals of the storyteller performing it. The tails are also short, minimizing their presence as the storyteller is trying to minimize theirs and blend in with the story itself.

At times, we also see the story come to life, where the visuals depict what is actually happening in the story. Here, because we are already immersed in the visuals, the balloons appear thinner to convey less separation. The font is also a little more plain to allow us to focus more on what is happening in the panel. Here is a great example of lettering guiding the transition from the latter mode to the former mode. We start immersed in the story and transition out of the story facilitated by the lettering.

Next, there are critics and audience members reacting to the story being told. These are signified through double-outlined, rectangular or more boxy balloons. They convey an extra layer of distance and clear separation from the story.

Then there are sometimes memories or flashbacks that Akane or another character has while they are telling the story about the time they learned the story or a time that thematically syncs with the story being told. This requires the readers to be immersed in a third setting, different from the performance and the story, while still maintaining our immersion in the other two. These sequences are portrayed through heavily-inked, black panels with greyscale, often textured figures and backgrounds.

It is clear that this is a vision or isolated sequence because of both the narration and the visuals. It takes place in a contained setting in someone’s mind, outside of physical space and time.

During a given performance, Suenaga and Moue transition from one perspective to the next and back again several times, and it is always clear to the reader what is happening and who is talking, and the reader is able to move from the story itself to reactions surrounding the story while still staying immersed in the overall manga. That requires immense care and collaboration from the entire creative team.

Finally, Akane Banashi isn’t afraid of its own jargon and technical qualities. While many sports manga will often fill in details about terminology associated with their sport, it is often only so that the reader feels more accustomed to the action on the page and familiar with the story being told. In this way, nomenclature is a means to an end. This is especially true for individual sports. In Blue Box or any of the other badminton manga out there, you almost never see drills or depictions of practice meant to narrow in on improving a specific technique. The overwhelming bulk of the sports narrative is geared toward competition, so most of what is shown on the page are matches or scrimmages. Team sports occasionally include a little more in order to emphasize a character’s particular role on the team. For example, in Haikyuu!!, a character might attend a receiver training camp because they are known as having a receiver role on the team or because they are known for having a weakness when it comes to receiving. In baseball manga like Ace of Diamond, all positions have unique responsibilities, so there is a bit more emphasis into the intricacies of being a pitcher vs. catcher vs. first basemen.

Rakugo is performed alone, so it would be considered an individual sport, but it is not afraid to get technical with various elements of storytelling. Additionally, the nature of its style of competition is so fluid that the manga can create or dissipate natural competitions a lot more seamlessly. Most sports have fixed, scheduled tournaments and matches. A rakugo competition only needs a couple performers in the same location, a restaurant, bar, or other casual venue to perform, and a willing audience. This allows for excursions that dive into niche elements of vocal storytelling such as particular styles of inflection, emphasis, gesturing, or even different ways of telling the same story that can afford to keep a reader engaged while getting specific with different storytelling techniques and seamlessly building to an impromptu competitive performance at the end where the technique can be applied.

All of this being said, Akane Banashi does succumb to a few classic pitfalls of the sports manga genre in ways that could hold the story back as the manga remains ongoing. They are all connected to what can be deemed “The Prodigal Protagonist.” It’s pretty straightforward in that a lot of what makes Akane so compelling is that she is a prodigy. She is young, very talented, is eager to learn, and learns quickly. Aside from her primary motivation to pursue rakugo, these are the key characteristics given to her, meaning that if she loses her prodigal nature for too long, her characterization can easily fall apart. This relates to another common pitfall of sports manga: Akane is not allowed to lose. Most of the time, the nature of this pitfall is related to the inherent structure of single-elimination tournaments. In this particular case, however, it is related to a combination of Akane’s prodigal nature, the advancement timelines of several uniquely talented figures around her, and the lengthy time in between promotion ceremonies that seem inherent to rakugo. Promotions seem to come very rarely and at the whim of masters, giving the impression that if Akane doesn’t get a promotion in a reasonable amount of time, she may not get the promotion for a very long time or without a major change in the rakugo school’s hierarchy. This leads to another, related pitfall which is that Akane cannot afford to lose due to the damage it would do to her prodigal status and the delays that would narratively mean with regard to her promotion. The story at one point does try to exploit a loophole in order to move its way out of a corner, but in doing so, it sort of drops everything it was juggling at once and resets itself rather clumsily. Still, these are a few issues that stand out against one of the best ongoing shounen titles today, and these cliches never inhibit the moving power of storytelling from shining through, which is why I’ll always be glad to recommend Akane Banashi.

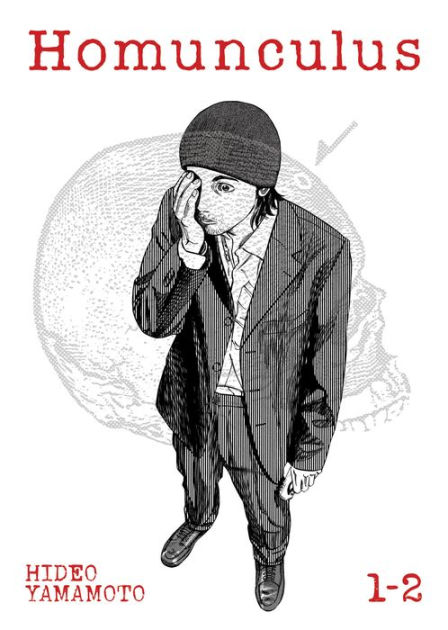

7. Homunculus — Hideo Yamamoto (W & A), Cerridwyn Graffham (T), Krista Grandy (Adaptation), Rina Mapa (L)

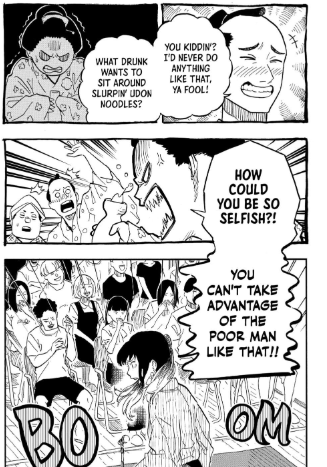

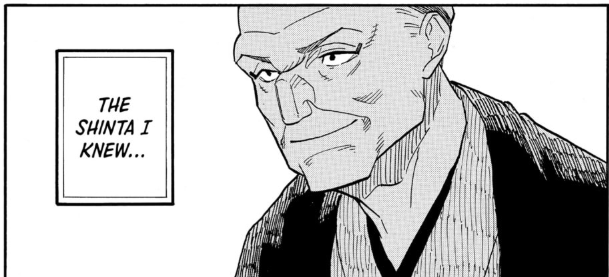

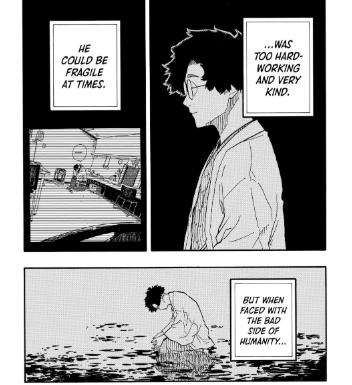

Is it possible to peer into someone’s soul? Is it possible to see your own soul? Hideo Yamamoto’s Homunculus attempts to answer these questions via a dark and narcissistic spiral into madness. There are a lot of comics that attempt to be transgressive as a shortcut towards an answer. If a comic is shocking enough, violent enough, or sexual enough, perhaps the reader will be more attentive and they’ll keep coming back. Shock value can have its short term benefits, but unless it’s done with care, it’ll only undercut the message in the end. Homunculus teeters along the edge of shock value for its entire 10 volume length. After all, trepanation, the core act around which the manga revolves, is quite graphic. I’m not sure I can say overall whether the manga’s transgressive qualities are theatrical or in service of something larger, but the manga evoked a lot of introspection, which is why it ended up on this list. I’m not sure Homunculus even comes close to answering its own thematic questions, but it does conduct a deep dive into their meaning through the motifs of penetration, barriers, and facelessness.

Penetration is the central-most motif of the three because of its relation to trepanation and the effects it has on Nakoshi. The act of drilling a hole in, penetrating, Nakoshi’s skull allows him to see into the souls of others, penetrating the flesh into another’s core being. When he confronts those whose souls he can see, they feel pierced and violated. People are notoriously very bad when it comes to judging their own ability to “read” others. That’s not to say it can’t be done or that no one has that ability, just that people tend to be unable to recognize it in themselves. It should sound familiar. I can think of countless times I’ve misjudged someone who I thought I had a comprehensive idea of who they were as well as many times where I was reaffirmed that some people were exactly who I thought them to be. On the other side of the same coin, there is nothing more vulnerable than when someone has an absolute read on me. The power of words is rarely more apparent than when someone says something that absolutely gets to the core of who I am, no matter how much I try to hide it or how much they may know me.

Homunculus tends to explore that motif in relation to the idea of love as well. If part of love is finding another person to whom one is comfortable bearing their soul, Homunculus often suggest the assertion that “reading” someone, penetrating their humanity without their consent, is akin to sexual assault. It never asserts equivalency, but the manga does ponder such a comparison rather assertively. Penetration is further emphasized through the manga’s hyper-realistic visuals as well. Whether it be the acts of trepanation themselves, or the frequent depiction of holes in people signifying a piece of them as missing or empty. There is also a large focus on people’s eyes and faces as the windows to their soul. Yamamoto draws very smooth faces, often with few large wrinkles but a lot of texture. Faces often occupy a lot of space in every panel, and Yamamoto relies on a large number of close-in shots to really zoom in on people’s eyes and expressions. The eyes are often drawn with extreme detail to give the sense that the reader is truly seeing into another human being. That is, unless the character has their guard up.

Barriers are the natural way to guard against unwanted gazes into the soul. Sometimes people put up conscious barriers, other times they are put up by the unconscious mind. When Nakoshi covers his right eye, looks at other people, and sees something unusual or grotesque, he interprets that as the other person erecting some sort of obstacle in order to not be truly seen. In doing so, however, the barrier serves as a clue into some of the existential difficulties that individuals may be struggling with. Some people appear surrounded by suits of armor, others as translucent constructs made of water. If Nakoshi is able to help that individual recognize parts of their inner truth, sometimes that barrier disappears and their soul appears the same as their external image. These might be seen as intrahuman barriers; barriers people put up in order to safeguard themselves.

There is also a lot of attention paid to the barriers constructed by society to divide people apart from each other. A large portion of Homunculus takes place in a portion of Tokyo where a single street divides one of the most expensive highrise buildings in the city from a park across the street with one of the city’s largest homeless encampments. Nakoshi used to be someone who frequented the highrise, a broker who made a fortune off of failing companies and the downfall of others. He was a willing slave to capitalism as he profited off of others’ ruin. Without notice, he quit his job and started living near the encampment in his car. He lives on the dividing line, anxious to eschew the moral bankruptcy of the rich occupants of the highrise while disgusted by the idea of completely giving himself up to the elements of homelessness he finds difficult to look at. As a result, Naskoshi sleeps alone in his car with a few remaining suits from his wealthy days. He’s able to drunkenly stumble into a campfire and share stories with other homeless individuals or find a public shower, clean himself up, and wander back into the highrise. He is welcomed everywhere but belongs nowhere. Just another faceless body in a sea of people.

Facelessness is the third and final motif as Homunculus ponders the human soul. There are a few people in Nakoshi’s life, including himself, for whom his new abilities only reflect back a person without a face. The manga, to varying efficacy, uses this facelessness to prescribe characters with a lack of self-awareness. The faceless are those who do not understand their own souls. Nakoshi’s soul, in particular, appears faceless for large portions of the manga, and as his self-perception changes, so too does the presentation of his homunculus. He transitions from seeing himself in no one, as an outcast, to seeing himself in everyone, realizing that no individual is truly special, and as he descends into a madness of his own creation, it becomes clear that relying on external procedures and actions directed at others is no way to to further understand the self.

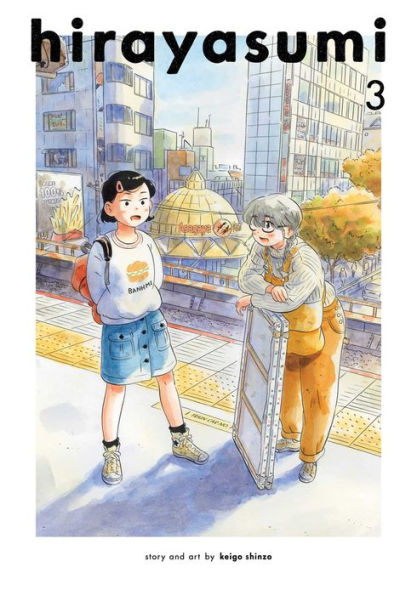

6. Hirayasumi Vols.1-3 — Keigo Shinzo (W & A), Jan Mitsuko Cash (T), Elena Diaz (L)

The biggest detractor to the quality of Hirayasumi is the ever-present knowledge that Hirato owns property that he inherited by befriending an elderly woman with no family before she died, and that this ownership enables his lifestyle. Outside of this inciting incident, Hirayasumi is a manga that almost instantly cements itself as a pillar in the slice-of-life genre. It stands out in its everyday nature, its joyful disposition, and its seemingly trivial but nuanced conflicts. Hideki is a former child actor, now 29 years old, who quickly burnt out and lost his passion for the art form. Now he spends his days trying to prioritize people in his life, because they are what truly matter, and looking after his cousin Natsumi, a new university student and burgeoning artist herself.

It’s fairly rare to encounter comics with a focus on characters in their late twenties, and Hirato is particularly relatable. He is someone who is looking to enjoy each day while also grappling with the reality that time is fleeting, those around him are undergoing large life-transitions that tend to leave him behind, and that just looking to prioritize the people in his life isn’t always enough. Hirayasumi largely exists to provide a sense of comfort, and it does so with art and layouts that are open with a sunny disposition and full of characters with cherubic faces. Still, I think that the manga shines as a reminder that even troubled individuals who are relatively lost in life can still feel joy; that just because there’s an underlying sense of worry doesn’t mean it’ll always show.

5. The Summer Hikaru Died Vols. 1-4 — Mokumokuren (W & A), Ajani Oloye (T), Abigail Blackman (L)

There’s a lot about The Summer Hikaru Died that is reminiscent of any rural high school paranormal mystery thriller. That may seem like a lot of adjectives, but it’s a fairly common genre. Still The Summer Hikaru Died manages to be particularly moving in select key ways that reflect a lot of intention and ability from Mokumokuren. It starts with the tagline: “What if your best friend (maybe something more) went to the mountains for a few days and came back… as something else”. It’s a hook that immediately reels in readers with its innate sense of mystery and a tinge of horror. It builds upon this through subtle infusions of setting, romance, and horror.

Mokumokuren deliberately placed the story in a remote part of Japan with rural housing, a tight-knit community, and in prefecture with a slightly eccentric dialect. There’s an ominous atmosphere overlaid atop a warm sense of comfort. For most people, gone are the days where children can freely wander to and from their neighbors’ houses at all hours of the day. Also gone are the times where children had equal community and environmental responsibilities along with their academic ones. Even though they are children, Yoshiki and his friends have a much higher level of ownership over their village than I’ve ever felt over my neighborhood or hometown. Even before any sort of presence or menace begins to show up, the village seems banded together, and once it does show up, it feels like that much more of a threat.

The community along with sparse elements of romance are what help the manga oscillate between false senses of security/hope and fear/unease. The escalation of dramatic tension comes from the fact that, from an external perspective, Hikaru may appear to be behaving strangely, but overall his close friendship with Yoshiki helps keep things relatively normal. In both public and private, there are plenty of discussions and situations where Hikaru and Yoshiki appear as best friends, but it’s clear from the very first scene that Yoshiki feels something more and that Hikaru once felt something more also.

Mokumokuren expressed fascination with the suspension bridge effect; the idea that fear and anxiety can sometimes also enhance attraction. This becomes apparent because of how sparingly Mokumokuren uses both elements of romance and horror. Yoshiki is in a very tenuous situation where he can except the loss of the person he loved, grieve, and the address the imposter as something menacing which forces conflict, or he can pretend that the entity in front of him with most of Hikaru’s memories, large portions of his personality, and the desire to remain Yoshiki’s friend, and maybe something more. It is a very tempting level of denial faced before the reader and this is even more enhanced by the moments of horror that coupled such emotional vulnerability. Physical intimacy during youth can be particularly scary, and I think that there are a lot of reasons why conventional exploration would never be allowed in The Summer Hikaru Died. Instead, Mokumokuren introduces the idea that inside of the imposter Hikaru is something evocative of eldritch imagery, and otherworldly substance incomprehensible to humans. The imagery is like stained glass or a butterfly pattern brought to life as slime. It expands and seeps out of the open wound when Hikaru is cut open and it sort of grafts around anything that it touches, and Mokumokuren introduces the idea that this incomprehensible, unknown creature feels good when Yoshiki sticks his hand in the wound. It is frightening and intimate and vulnerable and exploratory, and it is in these moments that The Summer Hikaru Died is able to display a complex vulnerability that transcends any of its peers.

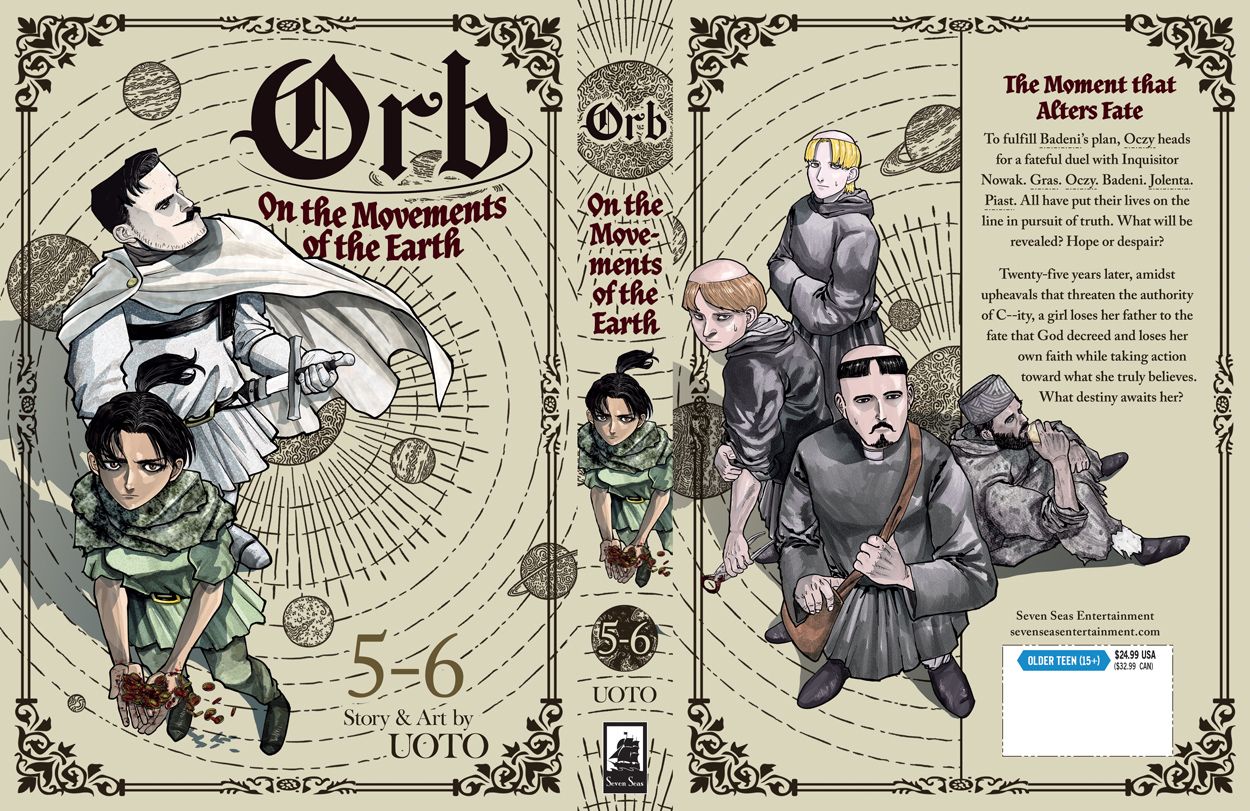

4. Orb: On the Movements of the Earth — Uoto (W & A), Daniel Komen (T), Molly Tanzer (Adaptation), Phil Christie (L)

Orb is the comic that, after my burnout on the medium, has resolidified exactly what my values are in the artform. I am more resolute in my convictions for storytelling above all else. There are a lot of comics written by talented individuals without the technical artistic craft to excel in all aspects of what they need to draw, but Orb has made me realize just how much I can overlook technical flaws in certain artistic elements if the capabilities required to enhance the narrative and characterization remain first-rate. Similarly it’s made me think back to the number of comics I’ve read from artistic masters with unbounded visual complexity filled with characters I couldn't care less about, leaving me unexcited as I turn the page.

The night sky is truly a marvel to behold and an exquisite natural phenomenon I know I often take for granted. In my brief time reading comics, I think I’ve seen countless renderings of the night sky with various degrees of complexity, but none have ever made me pause in such wonder as Uoto’s grayscale renderings with twinkles of white stars. I’m not sure how difficult it is to actually create such a background, but to a layman like me, it looks relatively simple. Still, when Rafal or Oczy or Badeni or Jolenta or Draka stare up at the sky and marvel with unbridled passion and curiosity, I sit back in awe, and I weep.

Orb stands out first and foremost for its intentional use of a eurocentric setting to explore a rather unusual subset of historical subject matter. Contrary to a number of manga content with the mere aesthetics of a medieval european setting in which to draw any flavour of generic fantasy or Arthurian world, Orb takes place in 15th century Poland and dramatizes the rise of heliocentric theory amidst the very resistant authoritarian power of the Church.

In choosing such a focal point for its narrative, Orb, in its execution, manages to depict a number of complex emotions that I have not seen rendered so clearly in any other comics. If I were to distill Orb into a single sentence, I’d say that it is about finding harmony between the rational truth and elevated faith and managing to find beauty in that harmony, but also in points of discord. The individuals who become passionate about heliocentrism do not do so simply in a blind pursuit of the truth, but in the consequential beauty and elevated sense of purpose they see within that truth. Many of them are not even directly antagonizing the institution that weaponizes faith in order to maintain a hierarchical status quo that treats large swaths of the population as lesser. They just see the beauty in heliocentrism’s natural simplicity. Never has comics made ration innovation so gorgeous.

This devotion to a beautiful truth leads the character to elevate the act of discovery as a priority that transcends the self, which only further reaffirms the manga’s beauty. Time and again, readers see ordinary people discover a phenomenon that shakes their world view and promises something more and do everything they can, sacrificing whatever they need to, in order to protect and preserve so that even one new person can carry on the research. There is no greater display of the power even small enclaves of individuals can have against an oppressive regime when they stand in solidarity with the means to preserve, conceal, document, and sacrifice. It’s an incredibly moving comic, however I would be remiss if I did not point out two critical errors in execution that undermine the very core of its story. The first is that of censorship. Uoto censors any word having to do with Christianity, Christ, or the Catholic church, as well as the country of Poland. This is likely because these entities are portrayed in an antagonistic, or at least controversial light. However, doing this only displays imagery of cowardice and undermines the bravery of the characters of the story. There is nothing more dissociative to the story. than reading a character insisting that research materials “blaspheme against the C--- faith.” The second is an error that I believe to be present in the translation/adaptation of the original Japanese manga. There is a character during the final act of the manga meant to resemble a character present during the first act. The latter character of great importance is named Rafal, and when the character mentioned very briefly at the end of the manga is named only once, the English translation also calls him Rafal, which adds a lot of confusion. In reality, fan translations have named him Rafael, which I believe to be a more appropriate and much less obfuscating choice. I have not been able to track down the Japanese raws of the final volume to verify that these two characters are not spelled the same way, but giving them the exact same name instead of closely resembling names would, once again, be a choice that needlessly obfuscates that core principles of the narrative. Still I encourage everyone to read Orb: On the Movements of the Earth, as it was the story that surprised me the most this year with how much I was moved.

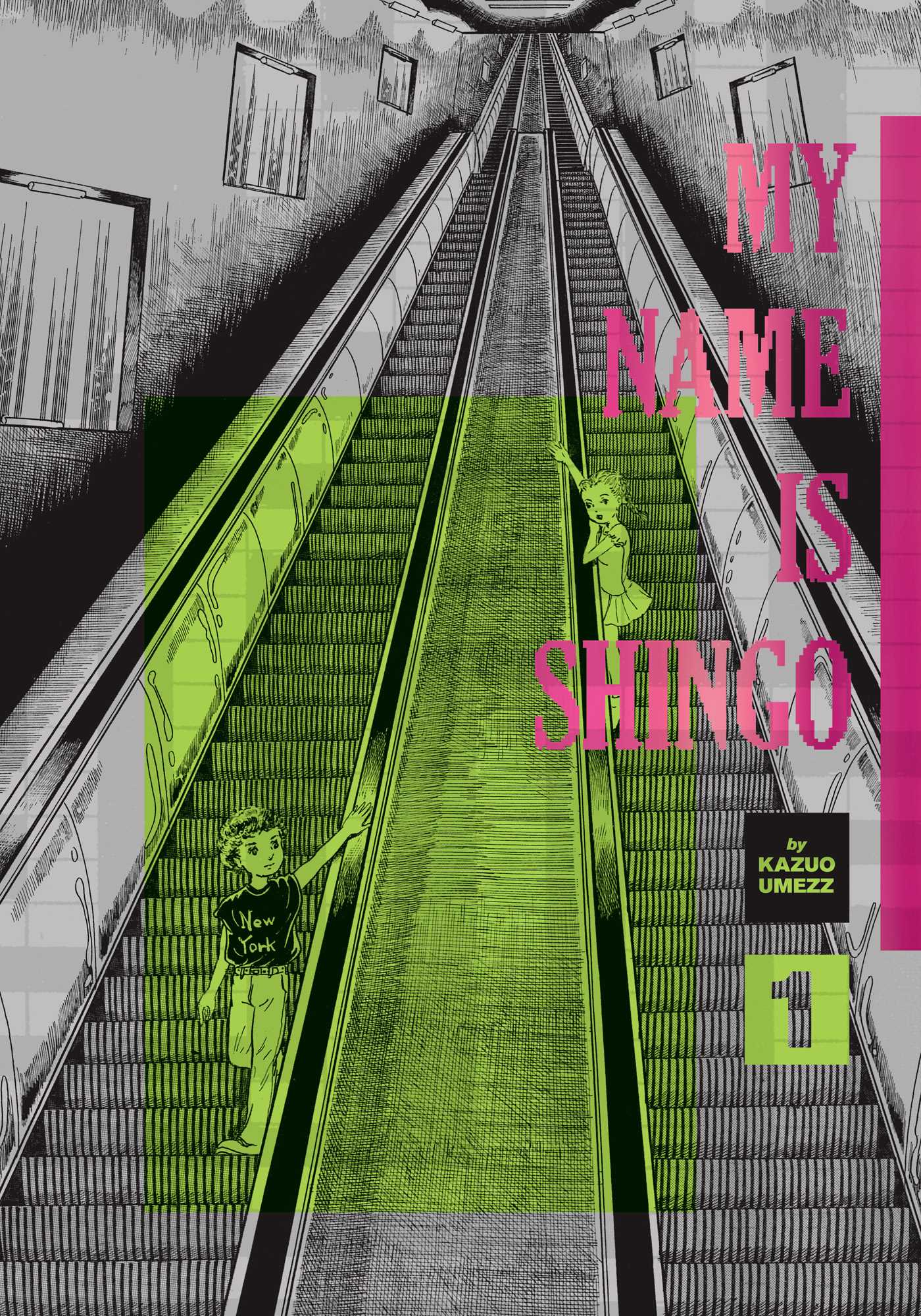

3. My Name is Shingo Vols 1-3 — Kazuo Umezz (W & A), Jocelyne Allen (T), Molly Tanzer (Adaptation), Evan Waldinger (L)

What happens when innocent curiosity becomes pinned down by the oppressive forces of emotional weight and the consequences of responsibility? The constraining environment in My Name is Shingo is enormous and intricate, but at the core of every page is a determined, innocent face that just wants to explore his, her, or its perspective of love. Satoru and Marin are two innocent children drawn to each other because of their shared loneliness and mutual interest in play, exploration, and the frontier of technology. Their love is non-sexual and kind. It is a love of company, a connection between isolated souls.

Around them are the complex realities of adulthood. Umezz contrasts their faces, often drawn with exaggerated expressions of surprise, frustration, or enthusiasm, with extremely detailed natural phenomena like rain or windstorms, vast environments that show how easy it is for children to get lost in the world, and entangled webs of circuitry and electronics that show the incomprehensible powers of technology these children have to confront. In that way, Marin and Satoru are constantly trying to find their way to happiness and each other against the realities of adulthood trying to stand in their way. This manifests in the form of their parents and other adults in their lives, who claim that because they come from two different worlds, two socio-economic classes wildly different from each other, they must not associate with one another. They claim that Marin’s selflessness and Satoru’s rambunctious curiosity are detrimental to society and themselves rather than tools for good. Still in spite of this, Marin and Satoru are able to spend some time with each other and, in doing so, create a child in the form of a conscious industrial robot named Monroe, before they are driven apart by forces beyond their control.

Monroe isn’t abandoned by Satoru and Marin’s choices, but rather by the forces of an unrelenting and uncaring industry that fears progress and the powers of competence. Monroe is a blank slate, a child who just wants to be with its parents again, but one living in the body of a machine with enormous strength and a level of computing power that may seem simple now, but can still learn and act in ways that humans can’t comprehend. If these themes seem complex, that’s because they are, but none of this is portrayed through dialogue. My Name is Shingo is an illustration of the complementary powers of text and imagery, as the text, often in the form of innocent exchanges between children or oversimplified criticisms from adults, serves to present an emotional core that the art expounds upon with uninhibited emotional entanglements. Perhaps this isn’t as reminiscent of the manga that made Umezz the legend he’s revered to be, but I find nothing more terrifying than a world constructed to harm children seeking companionship and understanding and abandonment resulting from the victories of the tormentors.

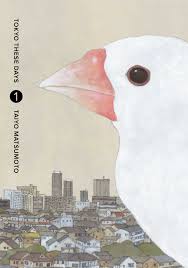

2. Tokyo These Days — Taiyo Matsumoto (W & A), Michael Arias (T), Deron Bennett (L)

There are moments in the creative process when your soul feels like it has been freed from its confines; when pure expression flows onto the page and you are able to shine rays of truth and beauty onto the world. Those moments are seldom, few, and far between. Most of the time, creating art is a motherfucker in an industry keen to watch you suffer. Tokyo These Days shines that hard, beautiful truth unto the world. The manga oscillates between a number of creatives at the twilight of their careers for one reason or another, most of which being that the industry has beaten them down. We start with, and primarily focus on Shiozawa, an editor who has fought the tenuous battle between what will sell and what has artistic merit for decades, and he is tired.

Any aspiring creative that looks to distribute their work to a wider audience dreams of that work remaining true and holding to its vision throughout the creative process. It’s not necessarily a refusal to compromise or listen to edits but a determination to remain true to the creator’s self and original principles.

If only that were possible most of the time.

Shiozawa is fed up with being the bad guy and has the ability to scrape together the means to have a chance at publishing a work on his own… because even a lifetime in the industry doesn’t buy you a guarantee. The question posed is: Can it be persuasive enough? Is the power of the craft inspirational enough? Everyone we see in Tokyo These Days is not merely an artist, because no one is merely an artist. That may be an aspect of who they are, but they also have lives. They live in or around Tokyo. They have bills to pay, and as many have found out, realizing their passion pays shit.

In a lot of my pieces, I have proselytized the power of storytelling. I believe that the power to move others through narrative is a great one. I believe that it can organize, motivate, call to action, and shape minds. But do not mistake this for naivety. I do not believe that storytelling alone enacts real change or shapes real lives. Just like the stories themselves, their power alone is simply fiction. It does not pay the bills, and it cannot realize these artists’ dreams on its own.

This is shown largely through the environments we see around these artists. Cities are lived in, rooms are messy, bodies are worn and neglected, it still rains, umbrellas still fly away, relationships still fall apart. No level of romanticism in the creative process changes that. Comics will break your heart, kid. Devote your life to them and they’ll ruin your relationships, leave you broke and destitute, cause long-term damage to your physical and mental well-being, and only amplify feelings of loneliness and abandonment. Do not, under any circumstances, devote your life to this medium.

However…

If you truly love it, and can manage that love appropriately, resting circumstances for yourself in which you are able to create freely while still grounding yourself in the virtues of reality, there may be no greater beauty than your creation soaring out into the world. Tokyo These Days never espouses the beauties of reality as being greater than the beauties of the craft or vice versa, in fact, it sometimes argues that they act as opposing forces. But if you can force them to act in harmony, then there may be no greater road to contentment.

For a couple of years there I had brief dreams of the days I’d be able to get something published, quit my day job and focus on making comics or prose or whatever I could create for the rest of my life, but I’ve since dismissed those foolish ambitions and that innocent naivety. I do hope to publish something one day though, and I hope creative pursuits always remain a facet of my life but not all of it, or even most of it. That’s where they ought to be.

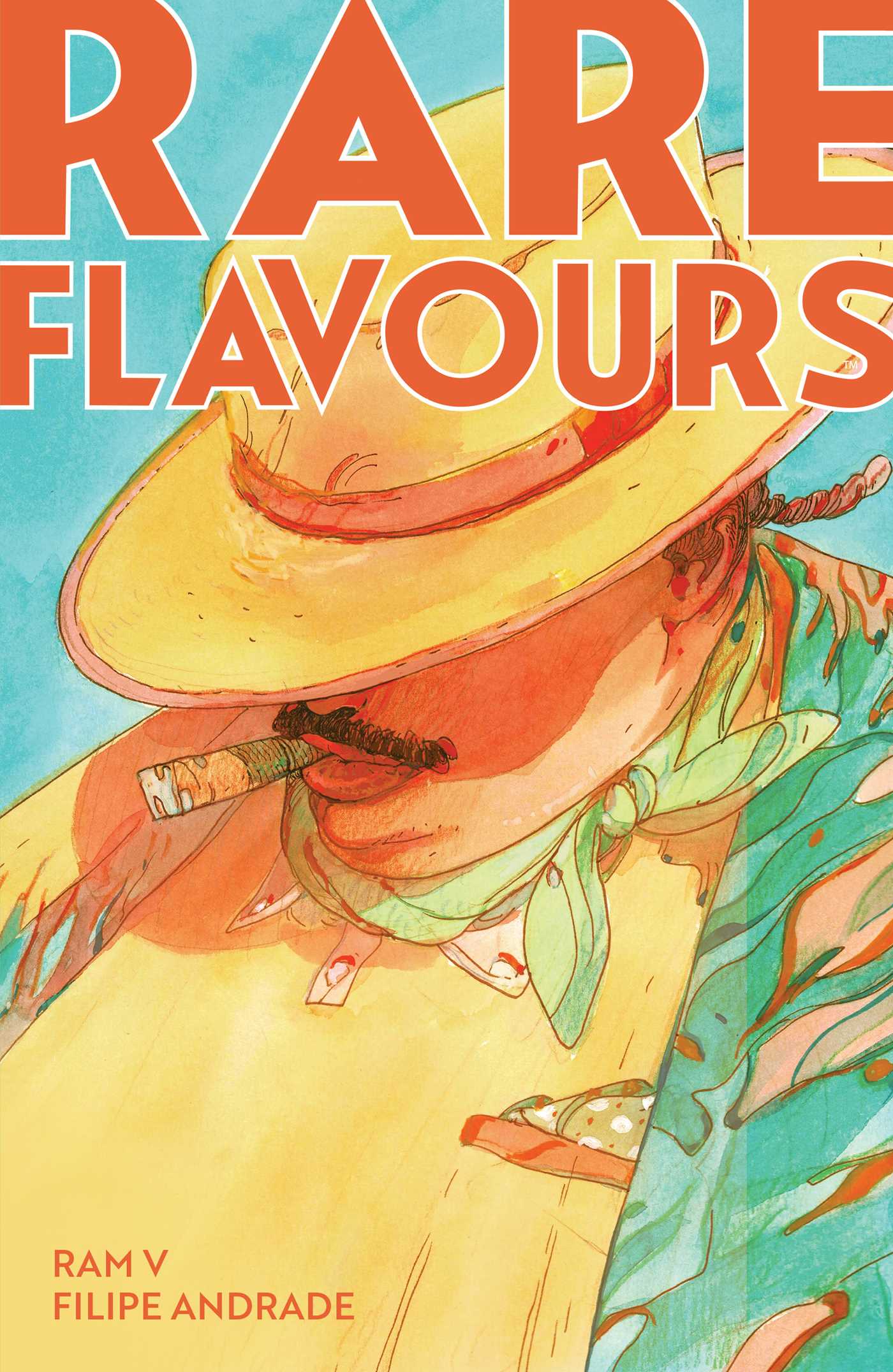

1. Rare Flavours — Ram V (W), Filipe Andrade (A), Inês Amaro (Color Assists), Andworld Design (L)

There are some cultural intricacies to Rare Flavours that I’m sure I don’t understand. This comic has the potential to come alive and capture reality for others in a way it does not for me, because I haven’t experienced any part of living, breathing, or eating in India. There is likely an intimacy that my soul can’t quite reach.

And still, Rare Flavours is my favorite comic of 2024.

I’m going to explore the ways Rare Flavours moved me through its superficial and thematic connections to a song that has also moved me immensely and that comes from a world away: “Lost it in the Lights” by the Wonder Years.

It was newly summer, and Tony Bourdain died.

Rare Flavours is a comic that emerges from the shadows of legends, those that once lived and those that live on through myth. The loss of great figures, literally or metaphorically, is such a sudden and destructive absence. But there’s something so profoundly special in our appreciation for them. There’s no replacing the bonds that form over shared emotions, even those of grief, of the powers of giving and lending a hand to others, and of the warmth that comes with receiving generosity from those around you. For as much sadness as they can bring, as heartbreaking as the loss can be when experienced alone, to share in both mourning and memory with others is inherent to the human experience.

I’m laying down in the shower staring up at a broken light. There’s something screaming out from in my vent at night.

It’s in the most quiet and isolated moments, when you’re all alone, that the darkest urges make themselves apparent in the deepest recesses of the mind. As much as we try to fight nature, loneliness and temptation are cruel adversaries, something that Rubin is deeply familiar with as even when he’s able to sample culinary delicacies far and wide, his appetite for human delicacies is never satiated.

From 50th and Cedar to Richmond off of Front, I guess I should be glad that there was any at all.

I think what I love most about the recipes in Rare Flavours is how simultaneously ubiquitous, universal, and yet also special they feel. No matter whether the recipe is placed within the context of being made by or for kings, rulers or demigods or as a dish crafted out of necessity by and for the masses, almost all of them exist today as a staple everyone is familiar with. The dishes are typically ones you can find in various forms and qualities almost anywhere, and what truly makes them special are the people that make them.

Both “Lost it in the Lights” and Rare Flavours emphasize life’s ephemerality. The magic found in the streets of Philadelphia or at a food cart on an unnamed beach in India may not be there if we were to visit them today. Locations are permanent, but people are transient.

The city coughs me out, like a splinter in my wrist getting pushed out of my skin.

For those who toil every day doing hard labor to make what entire populations take for granted, it’s easy to feel like nothing more than an irritation, something to be used and discarded, and I think that Rare Flavours shines a light on those people who are often treated as invisible by a ruling class that doesn’t want you to feel for those with little agency and by a consumer class of people who find it more convenient to live in ignorance of those sacrificed for their treats. Cities are an interesting thing in that they are last monuments built on the graves of millions, intent on overshadowing them and hoping that their lives are forgotten. Is that not the nature of urbanity?

When I was seventeen, I wrote a song about how I’m drinking kerosene to light a fire in my gut, and I’ll be coughing out embers for decades to come. I was seventeen with a fire in my gut.

Craftsmanship and artistry are labor. It is difficult and tiring to create, and the work, the wear it brings on the body and on the soul are things that often go unappreciated. Rare Flavours does not forget this, in fact, Rubin is often captivated as he describes how certain culinary traditions are precisely what bring out the flavours and elevate taste.

I think that through memory and intentional preservation, there’s a sort of melancholic sense of contentment that might emerge. An appreciation for life amidst the shadows of ruin. It’s painful, but it lights a fire in your gut. It propels you to keep moving forward. Even as you pay the price, even as you sacrifice a piece of yourself for the sake of that art and of memory against the temptations of ignorance, there’s still so much that drives you forward.

It’s almost inextinguishable once it’s lit. It always remains there, deep within the gut, so that even in their lowest moments, people are able to unearth an intangible hunger for the magic of creation, connection, and love that they were once able to capture and share.

It was right there waiting for me, I lost it in the lights. I guess I should be glad that I was still in the fight.

At one point in the comic, Mo asks Rubin why. Why, after living in hiding for centuries, did he decide to emerge once again out in the world? Why jeopardize his safety? No matter how isolated he kept himself, Rubin’s calling would not leave, and he did not know why. It’s so easy to consume whilst losing sight of the people behind the commodity, but Rubin hits the nail on the head when he emphasizes that the people are what save you. The food. The art. There’s no denying their powers, but they’re nothing compared to the people. To share your passions with one more person. That is always the true fight. It’s easy to lose that in the light.

CODA

Well, that was my 2024. I supposed if I really had to tie all together under a common thematic banner, I’d say that 2024 taught me:

Resist the monster; Embrace the self

It’s probably time I accept the reality that there’s a monster that lives in my head. It’s one constructed from equal parts doubt, loneliness, and apathy. It comes for me in times when I am most desperate; when it feels as though someone in my life who I’ve known for a long time or someone I recently grew anxious to know further starts slipping away. Since my lowest points of 2023 I feel as though I’ve lost countless people who I felt were of enormous importance to me, and yet I wonder a lot if I let them know that enough or if I was of any importance to them. What does it really mean to be important to someone anyway? There are people I see every day, who I probably take for granted, but there are people whom I’ve had a small handful of conversations with that have profoundly changed my life. I think about them all the time. Not of those conversations, necessarily, but them as abstract beings. Do other people operate like this? It’s not an easy existence, and I’ve really been working on verbally letting people know how much I appreciate them more, but it doesn’t get easier.

My default state is probably one where the monster wins if I am being honest. It’s just so easy for me to be unflinchingly uncaring, accepting of a life of small solitude sustained by consumption and the privilege of my positions. I cannot stress this enough how easy I find it to be unfeeling. It’s how I lived the first 18 years of my life. A lot of my favorite works of art in 2024 espouse the dangers that lie in the consequences of letting the monster win. The harm it not only does to you, but also to those around you. The invisible pains that reverberate into the world because of such a dark victory.

Luckily, there were also so many works that illustrated how rewarding it is to resist, to create in spite, and to fight every day to leave lasting marks of love and kindness in service of an artform or purpose beyond the self. I am fortunate that I’ve spent years determined to make resistance a habit, that I’ve built up the tenacity to be confident in my smallest and my power as a mere individual. I am not sure I’ve really found or shaped my purpose quite yet. It likely requires still more work to be done, but I got a lot closer to fully embracing myself this year, even when it felt like I lost a few of those who once showed me their embrace. To those who may be reading this, if you ever find yourself in moments where the monster is looking to gain the upperhand, and you need an embrace of another to help provide fuel for the resistance, please reach out and I’ll do what I can. I’ll see you in 2025.

EDIT: It’s now January 31, 2025. Things sure can pick up speed on the decline can’t they? It’s interesting how speedrunning towards the end of Empire provides some perspective. I can’t say my opinions on broadcasting have been completely altered, but I will say that whereas before the signal I sent out felt scrambled in a sea of noise, that same signal now feels like it’s being broadcast into a void. Even though more people are talking than ever, the chaos has tuned a lot out. So in that regard, I will say here, for anyone whose signal has been weakened, anyone who has been even further suppressed and harmed by a fascist and discriminatory administration: You matter. Way more than any of the art that I talked about above or the fiction that I share. I feel your broadcasts, and I will always do what I can to ensure their and your preservation.